(We're fortunate to have Ian Grace provide us with a wonderful biography of his late father, William Herbert 'Bill' Grace, and his mother, Clarice. As you'll discover, Bill worked

his way up through the ranks at de Havilland until he was coordinating the sub-contractors making Mosquito parts around London. Thankfully he passed his personal experiences on to his

son - Ed)

My father, William Grace, was born on 11th February, 1903 in Tottenham, North London - some 10 months before the Wright brothers flew.

In 1910, A. V. Roe was flying his AVRO Triplane over Tottenham marshes, having been evicted from Brooklands by the Clerk of the Course. Bill watched from below - the sight making a deep

impression on the 7-year old boy.

Young William's father was a third generation cordwainer - a master bootmaker - who went to France with the Cavalry as a leather worker and saddler. He was seriously injured and

returned to England, but was unable to work again. He eventually died of his injuries.

With three younger sisters and a mother to support, Bill was forced to leave school and go out to work as the family breadwinner. At the age of 13, he pushed a cart around the streets

of London in the early hours of the morning delivering milk. In time, he progressed through a variety of jobs, among them working on trams at a local terminus.

In 1920, he heard that there were jobs to be had at a nearby airfield where a new aircraft company was being established.

This was the de Havilland Aircraft Company being established by Geoffrey de Havilland at Stag Lane, Hendon, North London. Bill was taken on as a young apprentice.

In the early post-war years, orders were scarce and times were hard for the fledgling company. On Friday lunchtimes, the managers would sometimes take aircraft grade spruce and other

materials and sell them at the local market for whatever they could get for them in order to make up the wage packets on Friday night. But by the late twenties, the Moth had transformed

all of that, and the heyday of private aviation was in full swing. Records fell to Moths and many famous pilots were to be seen at Stag Lane. The company developed its first engine -

the Gipsy 1, and in 1927, Bill worked on the first pair of these engines on the bench. These two engines went into the two diminutive DH.71 Tiger Moth monoplane experimental aircraft.

By 1934, the company was booming and the Moth and other types were being exported worldwide. But the airfield at Stag Lane was being encroached upon by the spreading London suburban

sprawl. In 1930, the company purchased land a few miles north at Hatfield and established a new airfield. The factory was transferred there in 1934, with just the engine operation

remaining in the workshops at Stag Lane.

When war was declared, DH decided that they could best contribute to the war effort with a wooden fighter/bomber based on the technology of the DH.88 Comet racer and the DH.91 Albatross

airliner. That aircraft was the DH.98 Mosquito. Tiger Moth production was handed over to Morris Motors at Cowley, Oxford to make way for Mosquito and other production at Hatfield.

Early in the war, Bill was taken seriously ill with a ruptured appendixand was admitted to Edgware Hospital where he was placed on the critical list. One of his intensive care nurses

was Clarice Usher. Bill recovered - and married Clarice in 1942. He arranged for Clarice to transfer to DH's where she became an industrial nurse at Leavesden where, at the time,

Halifaxes were being manufactured.

Then, on the drizzly afternoon of 3rd October, 1940, Hatfield was bombed. A lone Ju-88 attacked the airfield at low level, dropping four bombs at such low level that they skidded across

the grass and tarmac and lobbed up into the old 94 shop which was crammed with workers and materials allocated to the production of the first 50 Mosquitos.

The damage was catastrophic, 26 workers died and many more were injured. Many died in a bomb shelter inside the building where one of the bombs exploded.

Bill was in one of the outside shelters, did a quick head count and discovered that one of his female workers was missing. He was sprinting across the tarmac back towards the hangar to

find her when the Ju-88 attacked. He was blown across the tarmac, but survived. (Bill was to die in 1975, partly from lung damage that was attributed to the bomb blasts that day.)

The Ju-88 came around for a second pass, and eyewitnesses stated that they were machine gunned as they ran for cover.

Anti-aircraft guns around the airfield opened up in response and damaged the bomber's starboard engine and tail. It staggered away, coming down at East End Green Farm at nearby

Hertingfordbury. The crew survived and escaped the aircraft, but were captured and spent the rest of the war in a prison camp in Canada.

Meanwhile, Clarice was waiting for Bill to visit her after work. By late evening, there was no sign of him. It wasn't until then that a neighbour told her "Didn't you hear? DH's got

bombed today." Bill finally arrived home at about 3 a.m. the following morning, covered in mud and blood. There had been chaos and carnage to deal with.

After the bombing, the manufacture of Mosquito components was dispersed. Being a relatively simple wooden aeroplane, over 400 furniture factories, garages and workshops throughout the

area were pressed into Mosquito component production. Bill's job was to co-ordinate this massive effort. By the end of the war, Hatfield had rolled out over 3,000 Mosquitos - a

tremendous achievement.

One perk of his job was that Bill had extra petrol rations because of the need to visit dozens of his sub-contractors. And if he made the odd private journey and got stopped, there

would always be a particular sub-contractor he was heading for!

On one occasion (after they were married), Clarice was being taken around the airfield in a Jeep. While waiting to cross the runway threshold, the driver noticed that the pilot of the

Halifax on short final had omitted to lower his undercarriage. The quick-thinking driver told Clarice to run out in front of the approaching bomber and wave him off. The driver was

wearing camouflage, but Clarice was in her all-white nurse's uniform. She frantically waved the oncoming bomber off - it overshot over her head at the last moment, went round, and

landed safely.

Clarice became a friend of Geoffrey de Havilland Jr. who was a test pilot for DH's. One day he offered to take her up in a Mossie.

Before she had the opportunity, young Geoffrey was killed in a Mosquito mid-air collision over St. Albans. It was strongly suspected at the factory that the fatal accident was the

disastrous result of a tail-chasing prank that went terribly wrong. Clarice never had her Mosquito flight.

Meanwhile Bill worked on at Hatfield under difficult conditions. The staff took turns in fire watching every night. He and a friend, when on the night shift in the deserted office

block, sometimes relaxed in Geoffrey de Havilland's office, smoking his cigars and drinking his brandy!

One night there was a bad fire in the Mosquito flight shed. One of the fire watchers was walking through the shed, among the latest group of production Mossies, when he noticed a slight

fuel drip from under the wing of one of the new aircraft. Seeing an opportunity, he decided that he could re-fill his cigarette lighter, so he opened his lighter and held it under the

drip. When it was full, he instinctively flicked the lighter to check it, and WHOOSH! Up went the wooden Mossie in flames!

At the end of the war, DH's laid off thousands of workers. Bill and Clarice bought a local tobacconist and confectioner's shop in nearby Fleetville.

Bill never learned to fly, but he maintained his aviation associations by joining the nearby Elstree Flying Club as a social member.

In the sixties, the hangar at Elstree was full of civilianized war surplus types - Miles Magisters, Messengers, Geminis, Austers, Proctors and Tiger Moths - not to mention Tim Davies'

Mk. IX Spitfire G-ASJV (MH434).

My parents would spend their evenings at the bar, but because of licensing laws, as a young boy of 10 years old, I was not allowed into the bar. So I spent these summer evenings sitting

on the bench outside with my Coca Cola and packet of crisps, watching the last aircraft land and be pushed into the hangar for the night.

When the pilots had repaired to the bar, I would wander through the cavernous black hangar and commune with the old aeroplanes, some still warm and smelling of hot oil and fuel.

Naturally, I was most drawn to the Spitfire, and to Mike Fallon's red and white Tiger Moth - G-AOIM.

Ian Grace

Ian added - What I didn't put on there was her story of the ghosts in the Leavesden hangars. Workers avoided the hangars at night, claiming that they were haunted by dead wartime

pilots. My mother always said that she didn't have the slightest problem with the ghosts who were all friendly and she often wandered through them at night!

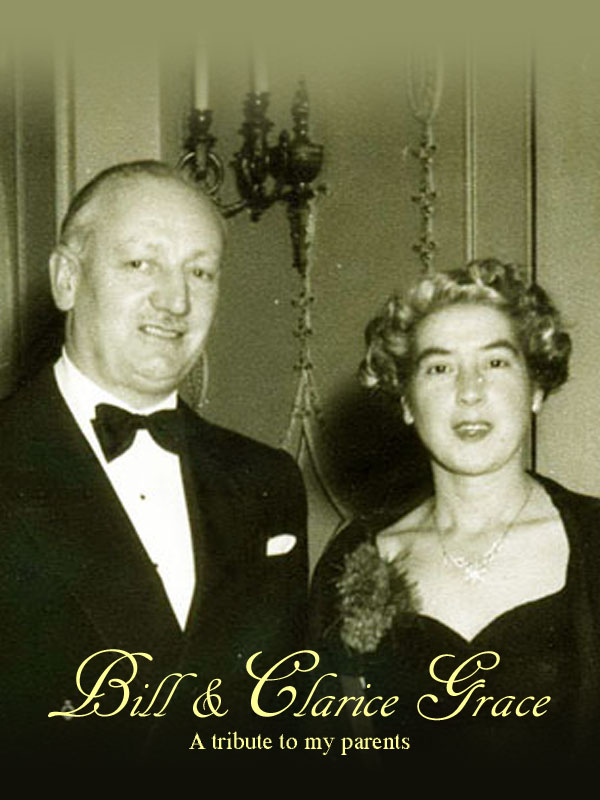

Both Bill and Clarice worked for de Havilland during the Second World War, and each had their own wonderful tales to tell. They met while Bill was in hospital and were married in 1942. Clarice became an industrial nurse with DH at Leavesden while Bill coordinated the production of Mosquitoes at some 400 sub-contractors. (Ian Grace)

Bill Grace's wooden tool box, which he made as an apprentice at Stag Lane using aircraft spruce, plywood, brass screws and alloy aircraft penny washers. Itís now a precious family heirloom. (Ian Grace)

A wonderful aerial view of Stag Lane in its heyday, just before its closure. In a few years, the factory had expanded considerably, but so had suburbia, which was to precipitate the closure of the airfield in 1934. While production and flight operations were relocated to Hatfield the shops were retained by DH for Gypsy engine production, but the grass airfield had houses built on it. (Ian Grace)

Compare this image of Hatfield in the early thirties with the previous one of the surrounded Stag Lane aerodrome. In the centre of the photo are the de Havilland School of Flying hangars and the clubhouse and swimming pool of the London Aeroplane Club. To the right, the first DH factory buildings are just going up. (Ian Grace)

A meeting of the Joint Production Committee at Hatfield in 1942. Bill Grace is seated third from left, in the pinstripe suit. At the outbreak of the war, Bill applied to the RAF to become a pilot, but was turned down because of the critical nature of his work at DH's. (Ian Grace)

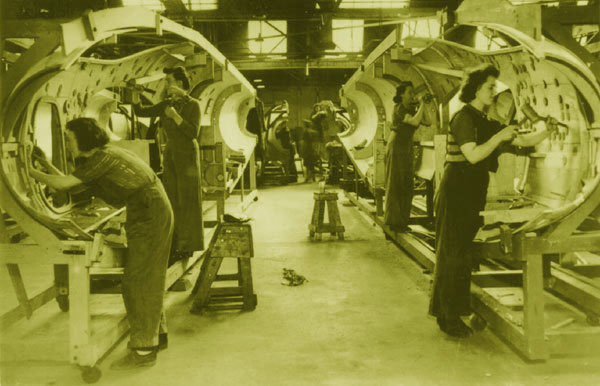

The unique design of the Mosquito meant manufacturing was very different from other aeroplane types. The fuselage was made in two halves - like a model aeroplane kit - each half was laid down on a massive wooden former on which was wrapped a sandwich of ply and balsa wood, giving the Mosquito its immense strength. The two halves were then fitted with their internal systems before being bonded together. (Ian Grace)

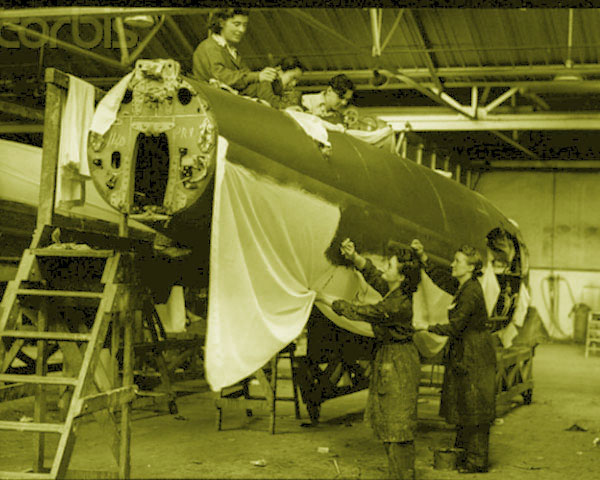

Once the fuselage halves were mated, the structure was covered in madapolam fabric. (Ian Grace)

A daring one-plane raid by a German Ju-88 bomber resulted in the complete gutting of 94 shop, along with the destruction of most of the materials allocated to the production of the first 50 Mosquitos. (Ian Grace)

The anti-aircraft gunners around Hatfield were able to exact a tiny measure of retribution against the German crew that attacked Hatfield. The men escaped the crash of their bomber but spent the rest of the war in a P.O.W. camp in Canada. (Ian Grace)

References: