I grew up listening to stories about the wartime exploits of various members of my family and decided that one day I would learn the complete story of each one. However, life, marriage and raising

children have a nasty habit of interfering with such plans.

One day after retiring, I dropped by to visit my mother and refresh my memory on some of the details in the stories. When she didn't answer the door, I entered to find her with a serious expression

on her face, staring at a pile of old musty smelling papers spread across the dining room table. She believed no one wanted her letters and wondered what to do with them. When I learned they were

from her brother Bob, I blurted out, "Lend them to me." Surprised at my interest, I explained I had already begun researching his story. They were like a gold mine, full of information, and

launched me on a decade long quest to discover more.

I knew that her brother became hooked on flying in his early teens, and had quit school in Grade 9 to work locally as an apprentice aero engineer after the Great War. At age 17 he persuaded

Calgary's Provincial Institute of Technology and Art, now known as SAIT, to start the first full length aeronautics course in Alberta and enrolled in it after lying about his age.

With the Great Depression underway and no flying jobs available in civilian aviation or the RCAF, Bob Niven enlisted in the Royal Air Force in 1935, where he excelled as a bomber pilot and

navigator. Three and a half years later he met Australian Sydney Cotton, an inventor and innovator who had made and lost fortunes a few times over. His adventurous swashbuckling style appealed to

Niven's rebellious side.

In 1938 British and French intelligence recruited Cotton and Niven for a scheme using an executive civilian aircraft to take clandestine photographs of German and Italian targets, and in early

February 1939 the first of three Lockheed 12A Electra Jrs arrived.

Imagine my surprise when I learned via the internet that one of the spy planes, G-AFTL, was still flying and was housed in an air museum in Kentucky with the American registration N12EJ. Many

people have seen it in the 'Howard Hughes Story', the 'Amelia Earhart Story' and television's 'The A-Team' and 'Doc Savage'. The museum put me in touch with a British photo intelligence

unit, who were enthused enough to voluntarily set up a loose-knit group involving various archives and museums to assist in my search. Apparently the full extent of Cotton's and Niven's exploits

weren't known, even to them.

That was about seven years ago and I've learned much about the Cotton-Niven story, that involved pioneering experimentation with aircraft, cameras and equipment. Before WW2 began their unit

photographed most of the Italian and German war preparations and military installations in Germany, Italy, the length of the Mediterranean Sea, North Africa and parts of the Middle East. Later they

photographed Belgium and the Russian oil fields in the Caucasus, then operationally photographed the Dunkirk evacuation and the German Blitzkrieg through the Low Countries and France. Trapped

behind enemy lines with his photo recon Spitfire during Dunkirk, Niven destroyed the aircraft and used disguises provided by fleeing refugees to escape to his base near Paris.

Research continued and my contact list grew, extending to Australia, Canada, the USA, England, Ireland, France, Holland, Germany, Belgium, Spain, the Czech Republic, the Ukraine, Russia, Afghanistan

and India.

Slowly, the story unraveled itself. From some of the gems of information, exciting new twists and turns emerged in the story. The names of Chamberlain, Churchill, Lord Halifax, Hitler, Mussolini,

Stalin, Goering, Kesselring and others began to crop up. Believe it or not, even Ian Fleming's and James Bond's names surfaced, and beautiful lady spies with nickname like 'Mata Hari' acted out

their own parts in the fantastic story.

There were arms dealers, secret agents in trench coats, a dummy or front company and a playboy-businessmen cover story. The German Gestapo and SS, French Deuxieme Bureau and England's SIS/MI5 and

MI6 were all in evidence. Secrets were stolen and exchanged hands. Cotton's Dufaycolor film company played a key role, with Germany's giant Tobis Corporation and Agfa films acting out parts of

their own. During one flight, Cotton and Niven secretly took photos of some of the most heavily fortified parts of Germany with enemy fighters flying off each wingtip with the unwitting high

ranking Luftwaffe officer, Albert Kesselring, at the Lockheed's controls.

Once war began, the RAF felt that military professionals could do photo recon better than civilian amateurs and dismissed Syd and Bob, allowing the Royal Navy to put them to work. After severely

embarrassing the Air Ministry by providing ample and timely photos for the navy, the RAF took them over. They were joined by another key character with the improbable name of 'Shorty' Longbottom

and used modified Spitfires for their wartime work. As the need for more intelligence became more desperate, the unit grew rapidly and future plans included a need for faster aircraft (initially

stripped down Spitfires) and some tests were done in mid 1940. Hitler trumpeted their success, when he berated Cotton's unit in one of his famous Munich speeches to massive crowds, and yet the

story continued on.

Eventually the unit became known as the Photographic Reconnaissance Unit (PRU), that became involved in every major and many minor actions during WW2. The PRU taught its methods and techniques to

their allies, and by the end of the war, there was a photo recon aircraft either landing or taking off roughly every 15 minutes somewhere in the world.

Cotton was dismissed from the PRU in June 1940 by aggrieved Air Ministry bureaucrats, who committed sabotage against another Cotton wartime project. Their efforts would have made German

intelligence and operational groups proud. Later they tried to trump up a charge of treason against him, but the personal intervention of Churchill put a stop to it. I began to wonder who the

real enemy was: Germany or the Air Ministry bureaucrats, and if early WW2 was more about in-fighting between the Air Force and the Navy.

Disgusted over how Cotton was treated by the Air Force, Niven and Shorty left the PRU a few months later.

Shorty became a test pilot and did much of the testing on the aircraft and bomb used in the famous Dambusters Raid, but was killed in a crash near the end of the war.

Niven left the PRU to do secret missions for the Ministry of Aircraft Production and the Atlantic Ferry Organization (Atfero, precursor to Atlantic Ferry Command), under fellow Canadians, Lords

Beaverbrook and Bennett. As the Commanding Officer of 59 Squadron based at North Coates, on 01 June 1942, Niven went missing while leading a diversionary attack for the first 1,000 Plane Raid over

Cologne.

I found it amazing to learn how a prairie dog from Alberta came to play such a pivotal role in pioneering photo reconnaissance with its world-wide impact, yet hardly anyone has heard of my uncle,

the spy:

Robert Niven wears his mess kit finest after completing his officer basic training at Uxbridge. From here, he'd move on to begin his flight training at Grantham - September 1935. (D. Lefurgey)

Adventurer, inventor, entrepreneur - Australia Sidney Fredrick Cotton was in the unique position to provide cover for the British and French government's clandestine efforts to photograph German and Italian military positions as the clouds of war began covering Europe. (D. Lefurgey)

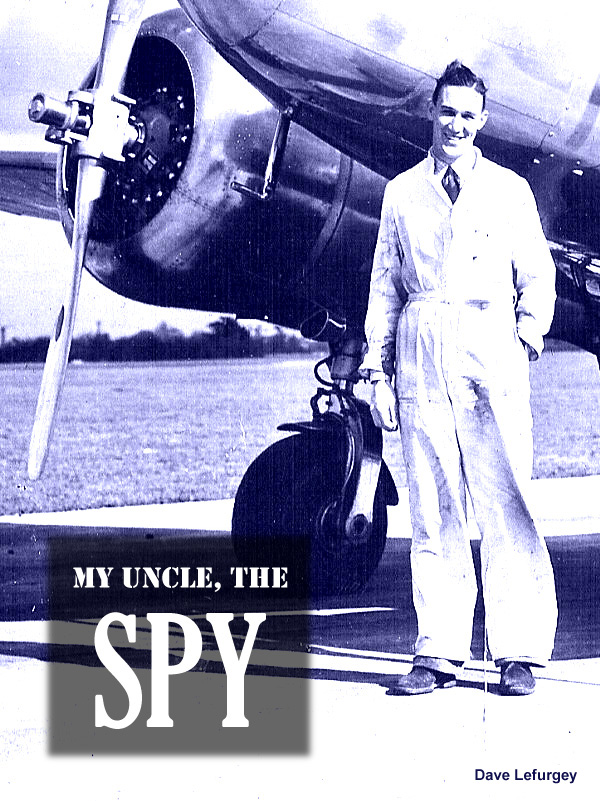

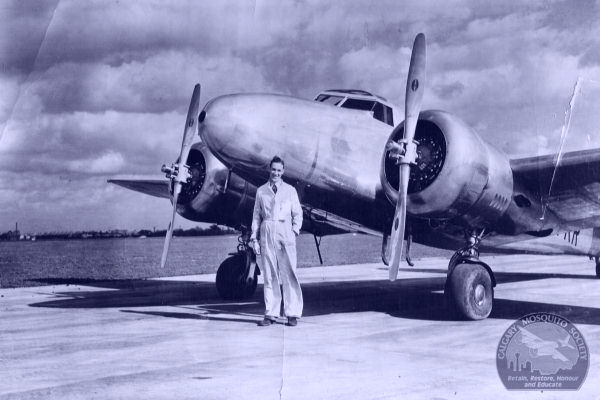

Bob Niven stands by their first Lockheed 12A Electra Jr., G-AFKR. Although it looked like a business plane on the outside, in reality it was a specially modified spy plane with secret compartments that hid a variety of cameras. This photo was likely taken in Corsica on Cotton's and Niven's first flight to North Africa about March or early April 1939. Cotton and Niven also flew Lockheed 12As G-AFTL and G-AFHN. (D. Lefurgey)

The attractive Andrea Johansen, who later married Bob Niven. She, and Pat Martin joined the duo on several pre-war spy flights where they operated cameras in the rear of the cabin. The secret of ducting warm air over the camera lens was accidentally discovered as they worked to keep warm. (D. Lefurgey)

Beautiful and just as adventurous as anyone else involved in the spy flights, Pat Martin helped her boyfriend, Sydney Cotton to photograph German military installations and later served as a spy in Italy. In reference to another famed female spy, Cotton called her "My Mata Hari." (D. Lefurgey)

At the start of 1940 Niven and Longbottom were the only Spitfire photo recon pilots in the RAF. By mid-February, Niven had trained about 10 more pilots who had experience in the PDU. They \ were the eyes of the RAF when Germany invaded France and the Low Countries in early May, 1940. Spitfire N3071 was the unit's first PR Spitfire, which Niven and Longbottom took to France in November of 1939 to prove operational photo reconnaisance. Contrary to popular believe they developed high altitude/high speed photo reconnaisance - not Cotton. (D. Lefurgey)

Likely taken in the summer of 1940, after he returned from Dunkirk, Niven is seen climbing into a PR Spitfire in this staged photograph (notice the dress shoes instead of flying boots). By this time the PDU was in Heston and its members being presented with medals from the King and Queen. (D. Lefurgey)