Hours after having taken off on a secret transport mission a lone Bristol Blenheim, its brown camouflage bleached by the North African sun, touched down on a captured Italian air field. As

its wheels began rolling the light bomber disappeared in a cloud of super fine dust and sand. Crammed inside were two Generals eager for their meeting with the advancing British Army.

Rolling towards a parking spot the pilot had an uneasy feeling in the pit of his stomach. Something just felt odd. Sure, with the British advancing across the desert 200 to 300 miles in a

single day it wasn't uncommon for the enemy to abandon their broken machinery but these trucks looked like they were still in use. As the bomber slowed they noticed small puffs kicking up

in the sand - this base hadn't been captured - and the tenants were quite unhappy about the unwelcome guest now paying them a visit. The pilot gunned the throttles and left the angry

Italians in his dust.

It was a close call, but for Sergeant Pilot Weldon Stacey, it was just another example of how disorganized the North African campaign was.

Born in Cumberland, BC, young Weldon grew up in Luscar, Alberta, a mining town so small that Weldon had to move to Edmonton in order to complete his high school education. "When I was in

grade 11 some of the other boys were signing up. I was in the (Army) militia, but I was only 18 in 1940... my father clamped down and told me I had to get my grade 12 first."

Armed with his diploma 19 year old Weldon walked into the enlistment office and signed on as an Air Gunner, a decision that resulted in a six month wait. It was while he was waiting for

classes to begin that a friend returned home, telling him stories of bombing missions over Germany in the back of a Shorts Stirling. "You're cold and you get shot at," he warned. Weldon

wasted no time remustering as a pilot in the RAF.

Weldon's journey from enlistment office to North Africa appeared normal - a stop in Brandon and Regina for training, learning to fly in De Havilland Tiger Moths and Cessna Cranes in High

River and Dauphin, and then specialized training as a night fighter pilot in Scotland using radar equipped Bristol Beaufighter Mk.IIs

While in High River Weldon became friends with another student pilot, Ray McKnight, brother of Calgary's famous Battle of Britain veteran, 'Willie' McKnight. "We always called him Bill,"

said Weldon, "but they called him 'Willie' for some reason." For the next two years Weldon and Ray would share their war, side by side, on three continents. But Weldon made the mistake of

showing off. "I tried buzzing the [Dauphin] tower." Rather than kicking him out the Wing Commander reprimanded his student, calling it a failed landing with the landing gear retracted,

followed by two weeks peeling potatoes in the mess. Ray received his Officer's commission, Weldon did not. "They told me I'd have been commissioned if I'd behaved myself."

Expecting to be asked to take Beaufighters to North Africa, Weldon and his classmates were informed that they wouldn't be flying. It seemed that every time a Beaufighter was sent to Africa

it ended up wrecked in an accident. Ground loops were very common. Instead, the next batch of pilots would travel by sea.

If peeling potatoes in Manitoba wasn't enough punishment then the trip to Africa was. "Ray, who was an officer, was on the top deck with the good accommodations and good food," Weldon

explained. "I, as an NCO, was down in the hold under terrible conditions." After making landfall in Nigeria the men traveled along a staging route to Egypt where they joined the Iraqi and

Persia Communications Flight. "When I got to Cairo I had my parachute bag and a small shaving kit. It took more than a month for my logbook (and the rest of his kit) to catch up with me.

It stayed on the boat and went through the Suez Canal."

On October 26, 1942, the skies exploded with artillery shelling from the British Eight Army - the second battle of El Alamein had begun. "The whole sky opened up and the next day we were

ordered to head all over the place... Montgomery looked after the Army but nobody seemed to look after the Air Force... for the first two weeks it was a real shambles for the Air Force."

Weldon followed Ray to Iraq, where Ray was commanding the airfield at Baghdad.

Assigned to a Comm. Flight meant one was expected to fly whatever had to be flown to wherever it was needed. Soon Weldon's log was filling with airplanes with names like Oxford, Wellesley,

Audax, Hart, Bisley and Bombay. One of the most ungainly aircraft he was assigned was the Vickers Valentia, a sausage-shaped biplane that looked like a left over from the First World War.

After dark the ungainly transport would take off and fly at 500 feet over the sand dunes. In the back was a jump master struggling to kick 20 horrified student parachutists into the dark.

In the open cockpit the two pilots man-handled control yokes two feet in diameter, struggling to keep the 10-ton biplane under control in the turbulent sky.

By 6:00am Weldon would usually be back in the cockpit of one of the Flight's Gloster Gladiator biplanes, climbing to 20,000 feet on a meteorological flight. Every 1,000 feet he'd record the

air temperature, making sure to pass it along to the meteorologists when he returned to base. Soon, the Gladiator gave way to Hawker Hurricanes transferred from the combat squadrons. "One

of my favorite tricks was to spiral down over Baghdad and swoop over the roof tops at about 350 miles per hour." With soaring temperatures, the locals slept on their roofs and were quite

irate about being woken up in such a manner.

From Baghdad, the Comm. Flight also employed the Hurricanes in a more combat-like roll. Ray, Weldon and another French-Canadian pilot would take the fighters on patrols looking for sabotage

to the oil pipelines, or performing the occasional night strafing mission along the highway. They never encountered any enemy airplanes. To keep their actions secret from the locals, the

pilots were ordered to enter any strafing flights as meteorological flights.

When Ray transferred to Burma, Weldon was commissioned so he could assume his friend's command. Besides the camel trains that refused to move, even when a speeding airplane buzzed five feet

over their heads, or the packs of wild dogs that ran rampant, another hazard was the local royalty. The Iraqi King was a seven year old boy who just had to sit in a Hurricane every time he

came to the airfield. Worried that the young King would accidentally retract the landing gear, Weldon would wait until the royal entourage left before jumping in the cockpit and returning

the switches and levers to their proper positions.

As the war moved away Weldon found his responsibilities changing. He continued to fly an assortment of missions; mapping all of Kuwait over the course of three days using a converted

Blenheim, a British photographer and a camera with a lens 10-inches in diameter, spraying and dusting for locusts in Southern Iran using DDT and a pair of specially-equipped Airspeed

Oxfords, or serving as the personal pilot for General Sikorsky of the Polish Army as he visited his troops. In Shabia he test flew an assortment of airplanes that had come out of

maintenance. "Some of them were pretty rough," he admitted. "Maintenance wasn't a very high priority. There was none (routine maintenance) in North Africa as I remember."

During one flight from Habbaniya, a chaffing ignition wire forced him to land his Blenheim in the Persian Mountains. Hindered by a dead radio, he waiting with his cargo of 124 cases of beer

for five days before he decided that rescue wasn't coming. With 'bush pilot' ingenuity he rewrapped the wiring and kept it from shorting on the cylinder with a block of wood. Aided by some

locals, he hand propped the engine to life and limped home to a commendation. On another flight, he spent two days waiting for an engine change on the dry river bed of the Tigress River,

not too far from where another generation of soldiers would one day discover the cowering dictator, Saddam Hussein.

In 1945, Weldon returned to Canada, where he joined No.1 Air Sea Rescue Squadron in Greenwood, Nova Scotia, flying Lockheed Hudsons (complete with lifeboats that could be dropped while in

flight) and instructing on Lockheed PV-2 Ventura patrol bombers. He volunteered to learn how to fly off aircraft carriers for the expected invasion of the Japanese home islands but the war

ended before the group began training in Florida.

When peace was declared Weldon, like hundreds of other pilots, applied to Trans Canada Airlines, only to be informed that his 1,400 hours wasn't enough - they wanted the pilots from Ferry

Command with a minimum of 2,000 hours. In the years to come Weldon would be a mink farmer, a pulp and paper maker, a flying instructor and an aircraft refueller. Like countless other young

men of his generation, he left the war behind and quietly went about starting a peaceful life back home.

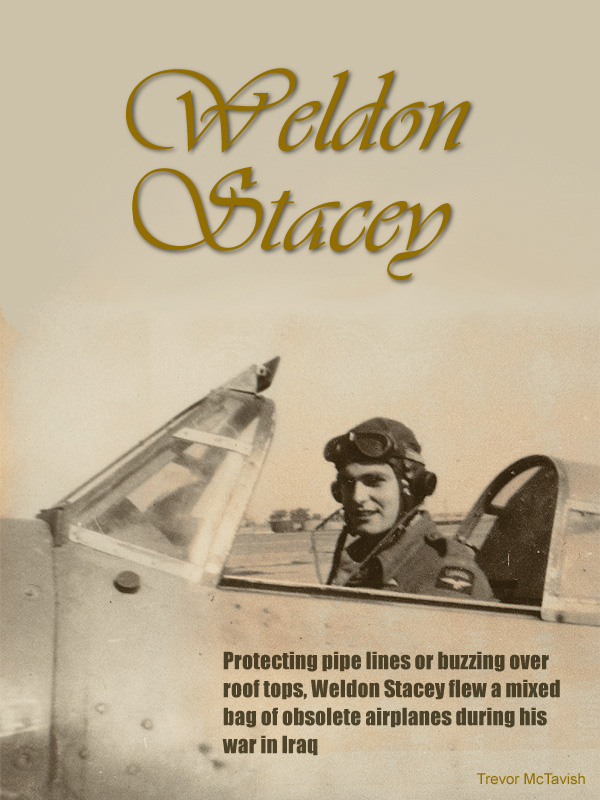

With a smile that shows his youthful exuberance, its hard to tell that Weldon was in the midst of the North African war. Thankfully that smile hasn't disappeared, even after more than 70 years. (Weldon Stacey)

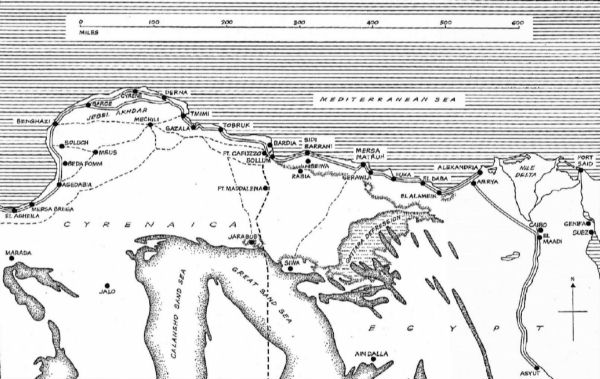

This map shows North Africa as it appeared in 1940. As part of the Iraqi and Persia Communications Flight, Weldon flew across most of the area on the eastern portion of this map. (www.btinternet.com/~ian.a.paterson/northafricamap.htm)

P/O Stacey in one of the Hawker Hurricane Mk.Is. Although they were war-weary hand-me-downs the Hurricanes were a quantum leap forward compared to the Harts, Bombays and Welseleys he'd flown previously. (Weldon Stacey)

Decades after the war had ended, Weldon received a fantastic gift. A handy-man hired to install shingles on his house was so enthralled by Weldon's stories that he painted this picture of one of the Comm. Flight's Hurricanes. (Weldon Stacey)