During World War Two, 52,818 Australians volunteered for training as pilots, navigators, gunners and 136,565 as ground crews in the Royal Australian Air Force for service in most theatres of

the war. They left to fight far away from their homes and loved ones. They came from the land, from sheep and cattle stations, factories, cities, country towns and brought with them that

unique sense of humour and devoted mateship that is the fierce pride of the Australian warrior. In the freezing skies over Europe, over 6,636 Australian aviators paid the ultimate price to

win a war. They came as boys, flew with Royal Air Force and if they survived, were old men by 30. When the war in Europe ended, 15,000 Australians had been involved in the air war against

Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy.

464 Squadron was formed in England in September 1942, and was initially equipped with the unsuccessful Ventura light bomber. This notionally RAAF unit comprised air and ground crew from

Australia, Britain, Canada and from across the British Empire. The unit was always cosmopolitan in nature and together with sister units 21 and 487 Royal New Zealand Air Force squadrons

comprised 140 Group of the Second Tactical Air Force. The three squadrons went on to fame as Gestapo and SS hunters. In September, 1943 the Squadrons had converted to the de Havilland

Mosquito known as the 'Wooden Wonder' or simply as the 'Mossie'. This aircraft excelled in a wide variety of roles including low level and high attack day/night bomber, long range photo

reconnaissance, minelayer, pathfinder, high speed military transport, long range day/night fighter and bomber. The Mosquito served in Europe, the Middle East, Far East and the Russian

Front. Of the 7,781 Mosquitoes built, 6,710 were delivered during the war years. No fewer than 27 different versions went into service and some of the most spectacular operations of the

air war were due to this moulded plywood wonder aircraft. At 437mph [728 kph] it was the most versatile twin engine propeller driven aircraft in the Second World War. Its wooden

construction made it more difficult to detect by radar than conventional metal aircraft and it could be flown at great heights at high speed which gave it almost complete immunity from

German anti aircraft guns and fighters until the advent of the German ME163 and ME262 jet fighters in 1944. It could carry phenomenal loads over extremely long distances performing feats

out of all proportion to the original specifications envisaged by its designers. The Mosquito was an outstanding warplane on every count but it was not without its problems. However, the

majority of those who flew in them loved them. Right from the start, low level intruder and precision bombing attacks became the squadron's speciality. Their contribution to the war was

invaluable but this little known unit is generally only remembered by the daring attacks on Amiens Prison, the Aarhus University and the Copenhagen Gestapo headquarters.

Jack Palmer and Jack Rayner had something in common apart from their first names. Both had originally joined the Australian Army, both somehow managed to transfer to the RAAF in 1942 and

both lived in close proximity to each other in the same state. Both went to Nova Scotia in Canada where they teamed up, passed their training courses and travelled to England for final

operational training at Bicester, which they completed with above average ratings. They would go on to be a very successful combination and complete a rare 47 day and night intruder

missions. In the world of combat crews, life was an attempt to escape the odds. They had the reflexes, instincts and natural self discipline to thrive, if they survived the first few

missions.

Just prior to 'Operation Overlord' the planned June 6 1944 D-Day invasion of occupied France, Allied aircraft were tasked to cause maximum delay to all enemy movement by rail, road or river

as well as their normal operations as a diversionary tactic. As part of the operation, 464 Squadrons Mosquitoes were to operate at night in an allocated area by either of two methods

depending on moon, weather and visibility. [1] By low flying attack with cannon, machinegun and bombs using the 'cat's eye' method. As night visibility was best in clear conditions under a

half moon, aircrews were kept in darked rooms during the day before raids or encouraged to wear light proof goggles to avoid bright lights that would ruin their night vision. [2] Similar

attacks but against targets that had been marked or illuminated by pathfinder aircraft. Operation Overlord was the greatest amphibious assault in history and the landing on the Normandy

coast was a great tactical surprise. Some 4,000 ships and landing craft carried 176,000 Allied troops and supplies across the English Channel escorted by 600 warships which supported the

assault with their guns. The RAF and the Eighth US Air Force played a large part in the success of the D-Day invasion by disrupting the enemy's ability to re-supply their troops.

The new boys in the squadron, Flight Lieutenant Palmer [pilot] and Flying Officer Rayner [navigator] arrived at the Squadrons base on Thorney Island [near Portsmouth, England] early

September 1944, and missed all the operations against the enemy both before and after the D-Day invasion and only began their first raid as a team on September 17 over Holland and North West

Germany. Flying Officer Rayner recalls their first operation;

"Our main job was to stop any transport, road, rail or river from bringing up supplies to the front. At briefing, crews were given an area to patrol and we left base at intervals between

2100 and midnight to harass transport in our area over a period of up to six hours. We flew in total blackout conditions and once we were over the North Sea and nearing the Dutch coast

which we regularly crossed at Egmond we would fly in a corkscrew action to put off any enemy night fighters. Once we were over the North Sea, you would hear the German radar picking us up.

You could hear it as a humming noise through our headphones. The volume would increase or decreased as the aircrafts' height went up and down. There was one place called Hilversum in

Holland where the Germans had a radar directed blue searchlight. The sounds of the radar carrying out a sweep in our headsets got more intense as we approached then suddenly there was a

high pitched squeal and the blue searchlight was switched on and caught us in the middle of the beam. Once an aircraft was targeted, several white searchlights would come and cone our

aircraft and the flak would start. We lost our night vision and couldn't read our instruments so essential for night flying. We escaped by putting the aircraft into a steep dive, doing a

screaming turn and were gone while they were still blindly groping around looking for us. Once we reached our patrol area, we were free to go where we liked within that area as long as we

made every effort to cross on our return, the coast at a point determined at the pre flight briefing. It was our exclusive entry door in which no-one else could use it. We used to see lots

of other aircraft go past when bombing raids were taking place and unfortunately with everyone flying around in the dark, there were many collisions."

October 2/3 was a highly eventful night for other members of the Squadron. A series of damaging attacks on enemy rail transport in the Osnabruck area resulted in three trains strafed and

bombed, a locomotive blown up and nine other trains hit. The two Jacks were also having some success of their own on the same night in the Emmerich-Munster area.

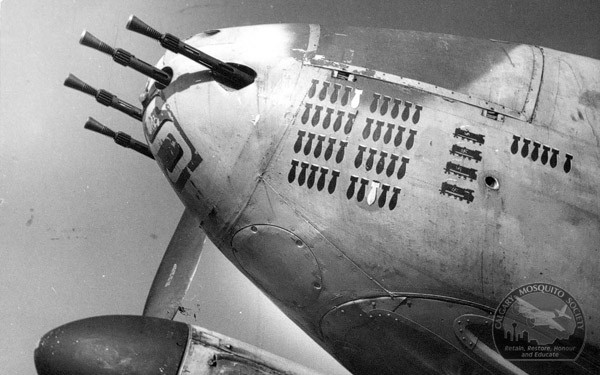

JR: "On railway patrol, we scored a direct hit on railway trucks in a siding, strafed two trains in the marshalling yard blowing one up. The nose combination of four .303 machine guns that

fired at a rate of 1,000 rounds per minute and four 20mm cannons at a rate 600 rounds per minute gave the Mosquito a very nasty sting. Mixed in with the ammunition were rounds of high

explosive, tracer and incendiaries so when we fired, the tracers could be clearly seen. When strafing with machine guns there was some noise whereas the 20mm cannons were very loud and

caused considerable vibration in the aircraft. In addition, we carried four 500 pound bombs. Sometimes on a really dark night, two one million candlepower parachute flares were substituted

for two bombs which enabled us to illuminate the target before bombing."

October 28. Jack Palmer and Jack Rayner strafed a train and destroyed a locomotive. The following night, four planes from the Squadron flew on a special mission. Their objective was to

destroy a train loaded with V2 rocket components spotted in a siding near Sneek in Holland. The attack was at low level with about a dozen strafing and bombing runs which were very

effective. The next night, the Jacks bombed barges and shot up a small ship in the Dutch Islands and Rhine Delta. The first night of November, they were at it again.

JR: "Sank one tank landing craft and forced the other to shore, cannoned a train, bombed another in the Zwolle/Arnhem area and a few nights later in the same place, machine gunned transport

trucks. It was here our luck almost ran out. The night was pitch black and as we patrolled we could see these coloured lights down below us so we went to investigate. As we got close we

were starting to get nervous and ready to get out of the area quick fast in case of trouble. Suddenly, it dawned on us that we were over the Zwolle German night fighter base with their

aircraft passing us. The only thing that saved us was that their anti aircraft batteries, 150 guns no less, couldn't open up on us for fear of hitting their own planes. Needless to say, we

got out of there fast!

December 16, 1944. As fog, rain and snow blanketed Allied aerial observation and hobbled combat capabilities, General Gerd von Rundstedt launched a surprise counter offensive in the

Ardennes area. The hard pressed Germans had secretly gathered an army of 24 infantry divisions, ten of them armoured and forced a V-shaped salient in between the British and American lines

at a weak point forcing the surprised and demoralised Allies back approximately 100 miles [161 kms]. Called 'The Battle of the Bulge' by the Americans and the 'Ardennes Offensive' by the

Germans, it was an enormous gamble by the desperate German forces to turn the tide of battle in their favour. The timing was unfortunate as it coincided with the worst winter in decades

making life and the conduct of operations extremely difficult for friend and foe alike. Thick fog across the battlefield hampering air operations in the first week of the offensive forced

even the redoubtable Mosquito to conduct operations elsewhere. On December 23, the two Jacks flew a mission to support the U.S. Army in the St Vith area and on Christmas Eve, flew another

support mission to St Vith. They may not have been able to celebrate Christmas in the Squadron mess but they did have their very own fireworks display on a grand scale, compliments of the

German army. They scored a direct hit on an ammunition train near Murlenbach just inside Germany. Their Christmas went off with a big bang. They supported the Americans again four days

later at Laroche.

January 1, 1945. While the fighting raged in the Ardennes, the German Air Force launched Operation Bodenplatte [Baseplate] a major offensive against all forward Allied air bases in Europe.

Every available combat aircraft was scrambled for the surprise attack. Historians differ greatly as to the numbers of aircraft lost on both sides, but a loose estimate of Allied aircraft

the Germans succeeded in destroying was approximately 122, mostly on the ground. The Luftwaffe lost 200 aircraft and irreplaceable crews. The result was a dismal failure for the Germans.

The Ardennes offensive lasted 31 days and resulted in an Allied victory and ended any chance of Germany being able reverse their military fortunes. The German war machine would never

recover and begin the down hill slide into the abyss of total defeat. In the meantime, 464 Squadron had moved to Rosieres-en-Santerre near Amiens in France. The officers' accommodation and

mess were established in the nearby Chateau de Goyencourt which was not as impressive inside as it was outside. Being a Luftwaffe base before the Squadron took it over, the Germans had

stripped it almost bare and left the new occupants a couple of nasty booby traps which were more nuisance value than anything else. The other ranks unfortunately had to live outside in

tents. During the battle when weather conditions permitted, 935 sorties were flown against the enemy hitting 74 trains and attacking over 1,000 wagons. As the fighting moved on, large

numbers of serviceable Tiger tanks were found abandoned. They had run out of fuel. Clearly, the Squadron had played their part in von Runstedt's defeat.

The Germans may have been down but they certainly were not out, so the Allies decided to 'to put the boot in' and kick the enemy around a bit more. On 22 February, 'Operation Clarion' was

launched and was to be the biggest single daylight operation of the war by Allied Air Forces. The Allied army was poised to cross the Rhine at Wesel and 'Clarion' was designed to stop the

enemy sending supplies and reinforcements to oppose the crossing. It was hoped that all forms of transport available to the Germans in a 24 hour period would be destroyed. About 9,000

aircraft from bases in England, France, Holland, Belgium and Italy attacked German railways, bridges, roads, rivers, ports and communication centres over 250,000 square miles [647.5000

kilometres] of enemy territory. The Jacks were part of the 16 aircraft the Squadron contributed to the operation.

JR: "We had an area south of the major port of Bremen. Tactically, we felt it was a badly organised operation because we had to fly in a group. We were number two. Navigation was

difficult and eventually didn't have much of an idea where we were. We came to a railway and followed it north strafing as we went. Suddenly, the outskirts of Bremen loomed up so we veered

south-west and bombed a train just west of Soltau scoring a direct hit on the engine. We strafed railway trucks in a siding at Verden, three locomotives at Langwedel and were shot at by a

flak train in a siding at Furstenaw. At Ligen we had our second close call and by sheer luck or divine mercy, lived to fight another day. We had accidentally flown between two

anti-aircraft gun positions and they had a go at us. It was a 90 degree deflection shot that hit us in the fuselage just in front of the tail. A magnificent piece of gunnery but

fortunately for us, the shell failed to explode. If it had, it would have blown the whole tail assembly off and it would have been all over for us. The shell made a hole in the main plane

severing the trimming tab cable to the elevator. We limped back to base at ground level which was bloody hard for Jack Palmer as without the trimming tab on the elevator, he had great

difficulty holding our aircraft straight and level. German night fighters shadowed us but didn't attack as we were too fast for them. We got back to our base at Rosieres-en-Santerre ok but

discovered on landing that only one strand of the elevator cable remained. During this operation, one of our pilots, a Canadian was shot down by an American fighter who possibly mistook the

Mosquito for a JU 88 or a ME 110 or so we thought at the time. The Yanks later tried to tell us it was a German in an American plane. We considered this utter rubbish! The Americans were

well known for their, 'shoot first and ask questions later' attitude. Fortunately the crew survived and were back in the air a few days later. However, later towards the end of the war one

of our squadron pilots, Gordon Nunn, found in a hanger on a recently abandoned German airfield outside Cologne, two fairly new fully armed Mustang fighters still in their American colours

which had been captured by the Germans. It was well known both sides had captured aircraft which were tested in the air for evaluation and comparison to their own. Perhaps in this case,

and with hindsight, we may have been hasty in our judgement of the Americans."

It is only speculative but these aircraft may have been part of the highly secret trials and research unit of the Luftwaffe called 2/Verschuchsverband Ob.d.L. This unit operated a number of

British and American captured aircraft including P-51s P-47s Spitfires and even a British Typhoon for testing, evaluation and operational sorties until April 1945.

JP: "I can't remember the date but one very interesting experience we had was with static electricity caused by lightening. We were flying through an electrical storm over Holland/Belgium

and you could hear the electrical interference on the radio and radar. Around the perimeter of the propeller, you could see static electricity building up. It began as a whitish colour but

as it danced up the wingtip it turned blue. It built up on the props and suddenly, there was a blinding flash and the static electricity jumped across from the engine across me to the

wingtip. I was blinded and couldn't see the instrument panel. The blindness didn't last long but it was certainly an experience."

The Squadron moved to Melsbroek in Belgium and in April 1945, the two Jacks began bombing operations over Berlin. Using specially constructed bomb bays to carry a 4,000 pound bomb, the

'Pregnant Mosquitoes' as they were called by the crews, flew missions every night over the dying capital of the Reich.

JR: "The Germans hated the Mosquito crews. When the weather was very bad and other aircraft were grounded, the Mosquito would still be up and it was business as usual making life hell for

the residents of Berlin. Air raid sirens, exploding bombs, fires, homes destroyed air-raid shelters full of terrified people and another sleepless night. We got such a bad name that a

report came through at one stage that if a crew bailed out and were caught, they would be cut to pieces. Nevertheless, the comradeship that had developed between us was due to the simple

fact that one's life depended on the other. One mistake and we were gone. Each of us had, by necessity, established a high degree of personal discipline."

The Squadron flew its last operation on 2 May and following the end of hostilities, flew the German Commander, General Alfred Jodl [later executed after the Nuremberg trials for war crimes]

to Berlin to sign the surrender agreement on behalf of Germany officially ending WW2 in the West at midnight 8/9 May 1945. Among other VIP's escorted by the Squadron were the British Prime

Minister Winston Churchill and Crown Prince Olaf of Norway.

JR: "One interesting trip we had was up to the Potsdam conference near Berlin. We were in charge of a flight of three aircraft and had to escort the British Foreign Minister, Ernest Bevin

back to London from this meeting. We left Melsbroek and flew to Gatow airport in the British sector near Berlin."

The Potsdam Conference July 17-August 2, 1945 was between the principal Allies to clarify and implement agreements previously reached at the Yalta Conference [4-11 February 45]. The chief

representatives were Premier Stalin, Prime Minister Winston Churchill [later replaced by Prime Minister Attlee who defeated Churchill in the British elections at the time] and President

Truman. The foreign ministers of the three nations were also present.

JR: "We arrived on the 31 July and were not due to leave until 2 August so a group of us with time off decided to go 'sightseeing' to see first hand the famous or infamous German capital.

The devastation was horrific. Quite shocking really! The city had been bombed so often, every night for the month of April and had only a few weeks earlier, suffered further terrible

destruction by the Russian military. The scene was ghastly and never to be forgotten. We only saw a handful of undamaged buildings; more than 90% were no more than burnt shells. We

visited the Reichstag, Germany's Parliament building and inside was ankle deep rubble with fallen ceilings mixed up with hundreds of thousands of Army record cards. We went into the wrecked

Reich Chancellery building which was just inside the Russian occupation zone and guarded by their troops. The lack of personal hygiene by the Russians was clearly evident. They went about

their natural business wherever they stood thus adding to the rubbish and causing an awful stench.

"We wandered around and in one room the floor was inches deep in a variety of war medals and ribbons in dirty envelopes that were being picked over by Russian soldiers. I managed to collect

a small box full of assorted medals including a silver Iron Cross and a special medal inscribed with Hitler's signature that he awarded to the mothers of German servicemen. As we passed the

Russian guard at the front door on the way out, he just stood there with his submachine gun and gave us the silliest grin I have ever seen. One of our Squadron members, Howard Purnell, had

previously been in the Chancellery building and got a set of Hitler's door handles. He is reputed to have been the first non-Soviet serviceman to enter Hitler's Berlin bunker after he

bribed the Russian guards to allow him in."

464 Squadron may have only been in existence for a short period but their war record is impressive. They destroyed eleven aircraft, 143 MT vehicles, 33 trains, one flying bomb, 24 tanks and

damaged six E-Boats, 138 barges and small boats, 2,396 MT vehicles and attacked 328 trains together with 743 stationary railway trucks. Add to this impressive achievement the precision

attacks on the SS barracks at Egletons and Bonneuil-Matours in France plus Gestapo HQs at Odense, the Aarhus University, and Shell house in Copenhagen, Denmark. The best known attack was

on the Gestapo prison in Amiens, France. This one hour raid which has now entered RAF and RAAF folklore as perhaps one of the greatest operations of the European conflict, freed political

and Resistance prisoners who were able to identify many Gestapo agents and collaborators responsible for their imprisonment, seriously damaging future German counter-intelligence efforts.

The Squadrons achievement can be summarised using the words from a note from the French Resistance five days later.

"I thank you in the name of our comrades for bombardment of the prison. The delay was too short and we were not able to save all, but thanks to the admirable precision attack the first

bombs blew in nearly all the doors and many prisoners escaped with the help of the civilian population. Twelve of these prisoners were to have been shot the next day... To sum up, it was a

success!"

After participating in a number of fly pasts, the Squadron flew to Fersfield in East Anglia and was disbanded on 24 September 1945. Both Palmer and Rayner returned home and back to civilian

life in Australia. Although they had been 'Mentioned in Dispatches' for meritious service during the war, further accolades were to come. On 6 June 2000, both Jack Rayner and Jack Palmer

were honoured by the French Government for their service in the liberation of France. The French Consul-General presented them both with a Diploma of Honour and a medal commemorating the

Normandy landing. This prestigious award has been presented to only a few Australians, most who served with the RAAF. A fitting recognition not only for their efforts during WW2, but also

in memory of all the aircrews and support staff of the Squadron whose efforts, 'saw the powers of darkness put to flight and saw the morning break'.

Ken Wright

Bombing up, Thorney Island, 1944. (Jack Rayner)

The business end of a Mosquito. Like the other Mosquitoes in 464 Squadron, SB-S was an FB.VI fighter-bomber. Armament was comprised of four Browning .303 (7.7 mm) machine guns, four 20 mm (.79 inch) Hispano cannons. It could also carry two 250 lb (113kg) or two 500 lb (227kg) bombs inside the bomb bay. (Jack Rayner)

The aftermath of a night time attack against a rail yard, seen in these daylight reconnaissance photos from September 6, 1944 (above & below). (Jack Rayner)

(Jack Rayner)

Group shot of 464 Squadron personnel, Thorney Island, Hants, October 1944. Flying Officer Jack Rayner is seated on the far right. (Jack Rayner)

A view of the officer’s accommodations and mess at Chateau de Goyencourt at Rosieres en Santerre. (Jack Rayner)

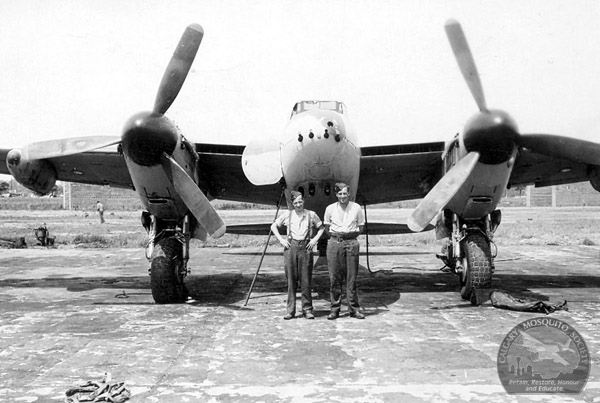

The two Jacks stand with their Mosquito, SB-J. (Jack Rayner)

A dramatic view of Berlin and the aftermath of the Allied bombing campaign. Jack Rayner later estimated that 90% of the city’s buildings were destroyed of damaged. Notice just how well the camouflaged Mosquito in the center of the photo is hidden. (Jack Rayner)

After peace was declared, members of 464 Squadron were able to witness the destruction of the Reich first—hand. Jack Rayner captured these images of the Reich Chancellary during his three days on leave in Berlin in July and August 1945. He later said of the city, “The devastation was horrific.” (Jack Rayner)

While visitng Berlin, Jack Rayner also witnessed the damaged Reichstag. (Jack Rayner)

References:

Australian Defence; Sources and Statistics, Joan Beaumont. Oxford University Press, 2001.

Personal memoirs and interview. Jack Rayner. Blackwood, Victoria, Australia.

Poetry extract, VE Day card, 2nd Tactical Air Force, RAF. May 8 1945.

Transcripts of interview. Palmer and Rayner. Courtesy Tess Egan. Montmorency, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Encyclopedia of Military History. R.Ernest Duput & Trevor N.Dupuy. Macdonald and Jane’s 1974.

J. Richard Smith. Eddie J. Creek. Peter Petrick. On Special Missions. 2005.

Kind permission:

Lex McAulay; Editor, Banner Books. Marybough, Queensland, Australia, for permission the use material from; The Gestapo Hunters. 464 Squadron 1942-45. Mark Lax & Leon Kane-Maguire. Banner

Books, 1999. Australia.

Peter Johnson for permission to use material from the 467-463 RAAF Squadrons History web site. www.467463raafsquadrons.com