Image the thrill, and the fear of being at the forefront of a night-time bomber raid. Flying so low over an enemy city that small arms fire and collision with buildings becomes your

greatest threat. Where split-second timing and precision flying would mean the difference between bombs on target or an unnecessary risk of lives. That was the life of the Pathfinder.

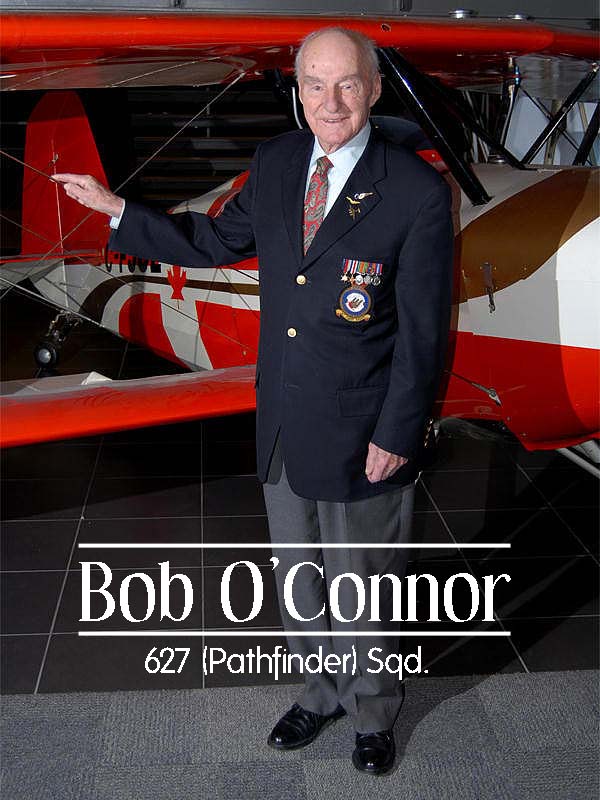

Like many of his generation, Bob O'Connor is a quiet man, with a quick smile and a glint of adventure still visible in his aged eyes.

Bob was a 15 year old farm boy from Penhold, Alberta when war broke out in Europe, but he knew that he wanted to join up and serve, but with an older brother driving trucks in the RCAF, a

sister in the Canadian Women's Army Corps. and two uncles in the artillery Bob's mother refused to sign her son's early enlistment papers. Instead, he waited until his 18th birthday before

hopping a train to Edmonton to enlist in the RCAF. It was Christmas-time, 1942.

Before enlisting, Bob (second cadet from the left, front row) was a member of No.7 Air Cadet Squadron. The roughly 200 teenage boys in the squadron came from four flights; two from Red Deer and one from Rocky Mountain House and Innisfail and District. Here, Bob's flight is seen during summer camp at No.7 SFTS, Fort MacLeod, Alberta, 1942. (Bob O'Connor)

After four weeks at No.4 Manning Depot Bob was sent across the river to the University of Alberta where he received 12 weeks of initial training at No.4 ITS. "That's where they started

figuring out what you were going to do," he explained. "It depended on what they needed at the time - and your qualifications." Of the 150 students at ITS only one was selected to become

an Observer, a combination navigator, gunner and bombardier. Most would be assigned to squadrons flying the de Havilland Mosquito.

From Edmonton the 26 men in the Observers class moved to Mountain View, Ontario, to begin two months of flight training; Avro Ansons for bomb training and Bristol Bolingbrokes for air

gunnery. Three of Bob's classmates were killed when the Anson they were riding in crashed. Five more months were spent in Chattam, New Brunswick, honing their navigational skills before

graduating as Pilot Officers. With that, Bob was off to England.

It was March 1, 1944 when P/O O'Connor arrived in England and was posted to 627 (Pathfinder) Squadron, beginning yet another six months of training, including three months using the Mosquito. The

squadron shared the airfield at Woodhall Spa with the famous 'Dam Busters' - 617 Squadron.

Although 627 was a RAF squadron, Bob was partnered with another Canadian from Pine Falls, Manitoba, F/L Dave Hutchison. Dave had been a flying instructor in England for two years when he

transferred to the squadron, but that still made them the junior crew, leaving them to take "whatever [aircraft] was available."

Finally the day arrived for their first combat mission - mine laying (gardening) in the Elbe River near Hamburg. Squadron Leader Oakley called the pair over to ask them some questions and

to try and alleviate their fears. "When you go to your briefing," he began, "you'll probably feel sick. Just look around the room, some of the old-timers will look just like you." The

briefing was in the afternoon followed by a special "operational" dinner that many called "The Last Supper". Dave and Bob then headed for their Mosquito to warm up the engines and check for

last minute squawks. Then, when the engines stopped and the okay was given, their fuel tanks were topped back up, a quiet time that lasted about 30 minutes. "That was probably the most

worrisome time, because you had time to think." And being 'tail-end Charlie' could only serve to worsen their fears.

"There was a tradition in the squadron, to piss on the tail wheel of your aircraft - for good luck." And with that, Dave, Bob and 11 other Mosquito crews took off into the darkening sky.

"We had two 1,250 pound mines," said Bob. "We had to go down quite low to make sure we got the mines in the water - about 300 feet." The mines were to be spaced 15 seconds apart. A small

parachute slowed them enough to keep them from exploding.

On route to the target Bob admits his fears disappeared. "As navigator you were really busy; you were always taking fixes with your radar - GEE. You were doing that all the way to the

target..." As the outline of the Elbe River appeared on the GEE, Dave turned the Mosquito to follow the river and dipped down to 300 feet. Bob, in the meantime, had unseated himself and

crawled into the cramped nose compartment where he released the mines. With their explosive cargo gone the Mosquitoes raced back towards the coast. "It was kind of exhilarating that you'd

survived," Bob admitted. But the squadron lost one Mosquito that night. "They made it back to the sea with one engine gone but it (flak) must have got his gas tank 'cause his other engine

quit." It was later discovered that the pilot survived and was taken prisoner. The navigator was killed.

Back home each crew was debriefed by an Intelligence Officer and given a fortifying shot of "good strong rum" and breakfast.

Reflecting back Bob admits, "The first time we did everything wrong, because of inexperience." But for their second mission, a gardening trip into the harbour of Bremerhaven, "everything

went smoothly." They were no longer the inexperienced rookies.

An important part of the Path Finder role was to accurately determine the wind speed and direction over the target before the heavy bomber force arrived. Each mission required 10 aircraft;

six 'markers' and four 'wind finders.'

The wind finders' mission took them about 25 miles away from the main target, one in each corner of the compass. As Bob explains the complicated process, "You'd start by dropping a

pyrotechnic that, when it hit the ground, would emit a flashing light for 15 minutes. You'd do a quick (timed 5 minute) orbit and when the cross-hairs of the bombsight crossed the light

you'd stop your recordings. You did this twice." The observer then charted his readings on a special piece of paper - marked out with concentric circles - each circle indicating 10

nautical miles. From the chart, the observer would get two wind speeds and directions which he then radioed to the senior wind finder, who averaged all eight calculations before radioing

the result on to the master bomber, another Pathfinder in a Mosquito. The master bomber then radioed the information to the entire bomber force before beginning to mark the target.

"It was pretty quiet for the wind finders." Even though the Mosquitoes were flying at about 5,000 feet, they were almost impervious to flak and fighters. With a large, easy to find stream

of bomber approaching the night fighters weren't wasted trying to intercept just one airplane, and as soon as the winds were radioed to the master bomber each crew was free to begin their

race for home.

By comparison, the Lancaster Pathfinders that accompanied the Mosquitoes were flying at 25,000 feet and were easy targets for night fighters.

Markings for a 627 Squadron Mosquito Pathfinder were included in a recent 1/48th scale plastic model kit. Being junior members of the squadron, Bob and his pilot flew whatever aircraft was available on the night of their missions. (Revell AG)

Bob's sixth, and final mission, was to an automobile or tank factory in Pilsen, Czechoslovakia. "Tally ho," announced the beginning of each bomb run, releasing two 1,000 pound bombs filled

with jellied gasoline. After each crew dropped their pair corrections would be made until there were 12 fires burning in the target area. For security reasons special additives made the

bombs burn a different colour each night. "You had to be pretty coordinated because the fires only burned for about 15 minutes. So you had to drop them about three to five minutes before

the heavies arrived."

While the marking factory in Pilsen was probably Bob's riskiest mission, it was during one of the quiet wind finding trips that Bob witnessed the only attempt at a night-time interception.

"They must have picked us up on radar," Bob said, obviously impressed by the determined German. "Because it was plywood the Mosquito didn't reflect radar very well." During their dash back

to the coast Bob would spend his time looking behind them watching for enemy fighters. "I don't remember picking it up on the MONICA (an aft-facing radar detector), so he must have been

getting vectors from the ground. All of a sudden I saw this streak of flame behind us." Fast, but poorly manoeuvrable with its ram-jet engaged, the pilot of the Heinkel He 162 Salamander

was helpless to counter the simple 360-degree turn that Dave put the Mosquito into. By the time he'd turned around, the Mosquito was gone - safely beyond another attempt at interception.

"We never saw him again."

Things changed rapidly when the war in Europe ended. Dave was returning home; he'd been overseas for three years and had a family and a job at the pulp mill waiting for him in Manitoba.

Bob on the other hand had just entered combat, so he volunteered for Tiger Force, the British and Canadian bomber force that was to participate in the invasion of the Japanese home islands.

Then came V-J Day.

Suddenly Bob found he was in a world at peace with the Canadian government ready to give its young men a chance at a future. "You could go to University; one month of school for every month

of service, you could take a cash settlement, or they'd buy you a 160 acre homestead and some equipment." With three years of service to his credit, Bob elected to go to University,

becoming a geologist just in time to witness the massive post-war Alberta oil boom.

When the Japanese surrendered on August 14, 1945, Bob, like thousands of airmen were preparing to head to the Pacific as part of the planned invasion of Japan. Although he'd volunteered for the posting, Bob's services were thankfully unnecessary. (Bob O'Connor)

Trevor McTavish